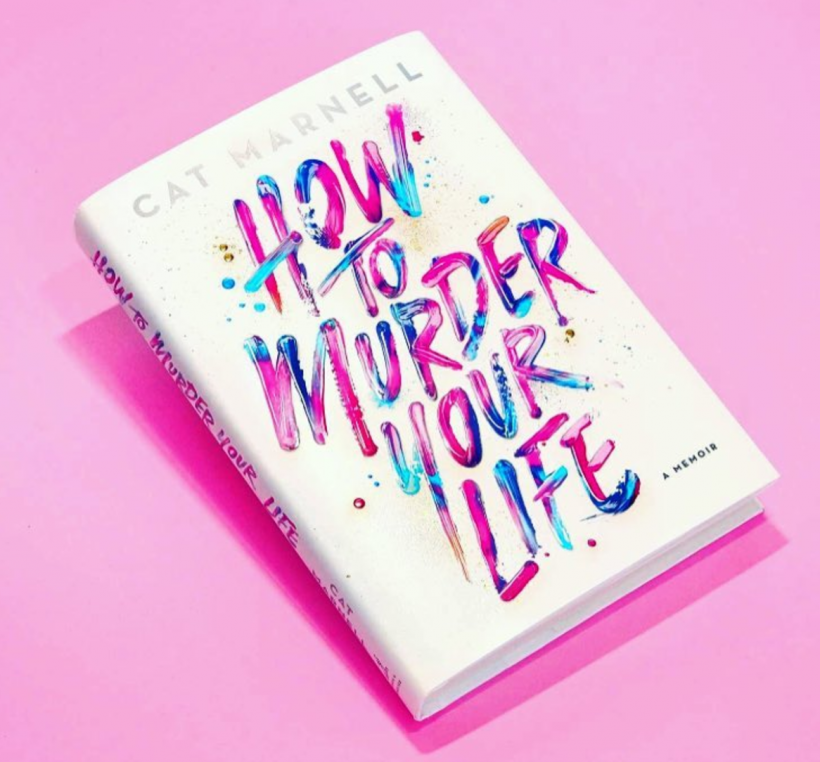

Cat Marnell: How To Murder Your Life

For those seeking safe, affordable and unencumbered access to birth control and abortion services, the political climate for reproductive justice in the U.S. and abroad has turned increasingly inhospitable in the months following Trump’s election. He expressed a desire during the Republican primaries to defund Planned Parenthood. He insisted that he would appoint pro-life judges to the Supreme Court, with the eventual hope that Roe v. Wade would be overturned so that abortion rights would revert to being decided by individual states.

And four days into his presidency, Trump signed an executive order to reinstitute the global gag rule, which prohibits foreign NGOs who are the recipients of federal funds from fighting for progressive abortion laws or counseling their patients about abortion.

Right now, for individuals who need to terminate a pregnancy, the lack of support has become downright hostile.

The Guttmacher Institute’s statistics on Induced Abortion in the United States claim that “As of January 1, 2017, at least half of the states have imposed at least one of five major abortion restrictions: unnecessary regulations on abortion clinics, mandated counseling designed to dissuade a woman from obtaining an abortion, a mandated waiting period before an abortion, a requirement of parental involvement before a minor obtains an abortion or prohibition on the use of state Medicaid funds to pay for medically necessary abortions.”

Given the legal and logistical obstacles, it’s nothing short of amazing when folks persevere against the odds to find a doctor and get to their appointment. And yet despite the hardships so many face in pursuing a legal medical procedure for terminating a pregnancy, there are ongoing forces that insist abortion is ultimately a story of darkness and suffering.

How to Murder Your Life is Cat Marnell’s tell-all memoir on her years of working as a beauty editor for magazines such as Glamour, NYLON, and Teen Vogue, while also hiding a severe prescription drug addiction — a story of “self-loathing, self-sabotage, and yes, self-tanning.”

For a time, she found notoriety in the NYC publishing scene after resigning from the now-defunct xoJane in order to hang out “on the rooftop of Le Bain looking for shooting stars and smoking angel dust.” She then briefly wrote the Vice column “Amphetamine Logic” before eventually going to Thailand for a lavish rehab treatment and then returning to the U.S. to complete her long-overdue memoir.

But as I parsed through Marnell’s exclamation-mark-infused, spiraling tale of debauchery and hedonism (much of which occurred in hotel suites and publicity events that were paid entirely on her publisher’s dime), it turned out that one of the most shocking aspects of her book was in her discussion of abortion. While enrolled in boarding school as a high school senior, Marnell becomes pregnant and soon learns that Massachusetts requires parental consent for an abortion. At fourteen weeks, she finally gets a ride to an out-of-state clinic, only to learn that this clinic “can’t proceed… We don’t perform second-trimester abortions in New Hampshire. It’s against the law.” It’s a heartbreaking moment that results in a few additional weeks of panic before Marnell’s parents are eventually informed by the school.

As an introduction to the scene on her second-trimester abortion (“Let’s say… eighteen weeks?” she writes), Marnell recounts the incident as follows:

“The only thing worse than getting abortions is reading about abortions. Am I wrong? Please skip ahead if you are squeamish. Life-murdering can get rather gory, you know.” (Emphasis hers)

So, all right. The premise has now been established by the author that abortion is “life-murder.”

Okey-dokey.

At a clinic in Washington, D.C., Marnell’s mother (who accompanies her to the appointment) declines anesthesia. As a result, Marnell describes a torturous, painful event that left her in tears:

“The procedure had been so awful. So violent. It looked like murder. It felt like murder. I’m not saying that in any kind of political way. I’m just telling you how it felt.” (Emphasis hers)

To that, I counter: Marnell cannot throw a literary grenade into the conversation on abortion and then claim it’s “not political.”

My first reaction when reading this story was remembering Jia Tolentino’s “Interview with a Woman Who Recently Had an Abortion at Thirty-Two Weeks.” Her 2016 interview is with a woman who goes by the pseudonym Elizabeth, who learns that her pregnancy is not viable — “if we came to term, he would likely live a very short time until he choked and died, if he even made it that far. This was a no-go for me.” The abortion ultimately has to be done in Colarado, requiring $25,000.00 and a cross-country flight from Elizabeth’s home state of New York, where abortion is only legal through twenty-four weeks.

At the end of the interview, Elizabeth says, “I can’t help but think about other people who have been through late-term abortions. I know that it’s not common, but it does happen. It makes me feel angry that we can’t just have an honest conversation about it — that we can’t talk about it scientifically or practically. It all has to be talked about in these couched terms that are ultimately religious…”

Couched terms like life-murder.

It’s absolutely possible to write about the regrets surrounding an abortion without giving into the rhetoric of the pro-life movement. In the article “5 Things I Regret About My Abortion (That Aren't My Abortion),” Priscilla Blossom wrote in earnest on how she regretted “being unable to speak about it as openly as I’d like… that my insurance company wouldn’t pay for any part of my abortion… that those who have abortions are regularly shamed for their choice.”

My problem with Marnell’s descriptions of abortion as awful and violent is that message is going to reverberate at a time when abortion rights are even shakier than they were back in her high school days.

We need more action and resistance to the notion that pregnant people’s bodies should be legislated. I wish Marnell had chosen to speak forcefully about a teenager’s right to choose; if the consent laws in her school’s state had been different, for example, she would not have been made to wait until her second-trimester to end the pregnancy. I wish that no teenager had to go through what she did — the uncertainty, powerlessness, and loss of bodily autonomy that comes with so many U.S. restrictions on abortion.